‘You have to breathe to live. But if you breathe too much, life become* dominated by fear of symptoms, and fear of living life to the full/

Hyperventilation means moving more air through the chest than the body can deal with. Most people have experienced hyperventilation – also called over-breathing – to some degree, usually in the form of an acute attack. It’s a normal reaction to sudden danger or excitement, and the signs are easy to pick.

- Breathing and heart rates speed up.

- Adrenalin pours into the bloodstream.

- The nervous system is on ‘red alert’.

- Muscles tense up.

Sometimes people faint or collapse – or find super-human reservoirs of strength. When the stressful event is over, the body returns to its normal relaxed state.

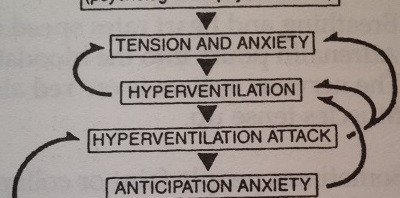

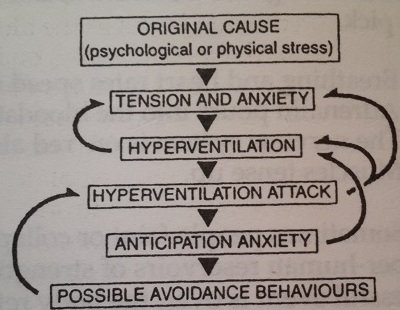

Less easy to spot is chronic hyperventilation, a

breathing pattern disorder in which over-breathing becomes a habit – usually in response to prolonged stress or tension. More widespread symptoms are felt, and at times these appear out of the blue. The symptoms may mimic serious disease or remind the sufferer of the perhaps frightening events surrounding a past acute attack. When this happens more widespread symptoms mysteriously occur.

- Breathlessness at rest for no apparent reason

- Frequent deep sighs or yawning

- Chest-wall pains

- Palpitations

- Light-headedness and feeling ‘spaced out’

- Tingling or numb lips or extremities

- Gut upsets or irritable bowel syndrome

- Achy muscles or joints, or tremors

- Tiredness, weakness, broken sleep, nightmares

- Sexual problems

- Clammy hands and high anxiety or phobias

cascade of symptoms

When over-breathing becomes chronic the balance between the oxygen-rich air we breathe in and carbon-dioxide-rich air we breathe out is upset: carbon dioxide levels start to drop.

Far from being just a waste gas at the end of the respiratory cycle, carbon dioxide is a powerful governor of many of the body’s systems – including blood flow to the brain. With chronic overbreathing the normal acid/alkaline balance (pH) of the tissues is altered. The body becomes more alkaline, and the nerve cells are the first to respond to this respiratory alkalosis. Dizziness and tingling or numbness are often the first signs.

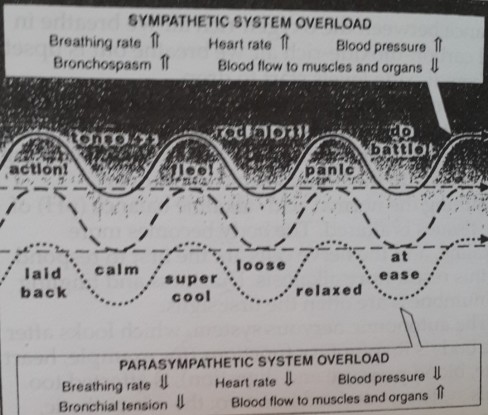

The autonomic nervous system, which looks after the body’s involuntary functions (for example, heart rate, blood pressure and digestion), is affected too. This system is divided into two: the sympathetic, which governs action and ‘get up and go’, and the parasympathetic, which is responsible for rest, recuperation and calmness. Low carbon dioxide levels stimulate the sympathetic nervous system more than the parasympathetic, putting the body on continuous red alert.

If carbon dioxide levels in the blood fall further with continued over-breathing, body cells begin to produce lactic acid in an effort to balance their pH. Muscles ache. Metabolism is less efficient.

Exhaustion and chronic tiredness soon follow, with feelings of physical and mental depression – all typical signs of long-term chronic hyperventilation.

Not only nerve cells are affected.

Muscle cells become more twitchy, and the smooth muscles of our blood vessels, airways and gut tighten and constrict in response to lowered carbon dioxide. There is an increased release of

Autonomic nerwus system, controller of involuntary body functions

histamines, which aggravates allergic responses. The heart starts pounding and the hyperventilator may feel panic-stricken, with palpitations and feelings of ‘air hunger’.

When carbon dioxide levels are too low oxygen clings to its carriers – the red blood cells – and tissues, especially the brain, become starved of oxygen. The brain may have its oxygen supply cut by as much as 50 per cent, making it difficult to concentrate, let alone feel part of this planet. The drop in oxygen supply to the brain stimulates the breathing control centre to increase breathing ** and the chronic nature of the hyperventilation is reinforced.

As the oxygen and carbon dioxide exchanges fuel every cell in our body, every system is ultimately going to be affected – leading to a distressing as well as puzzling range of symptoms.

Why does chronic hyperventilation happen?

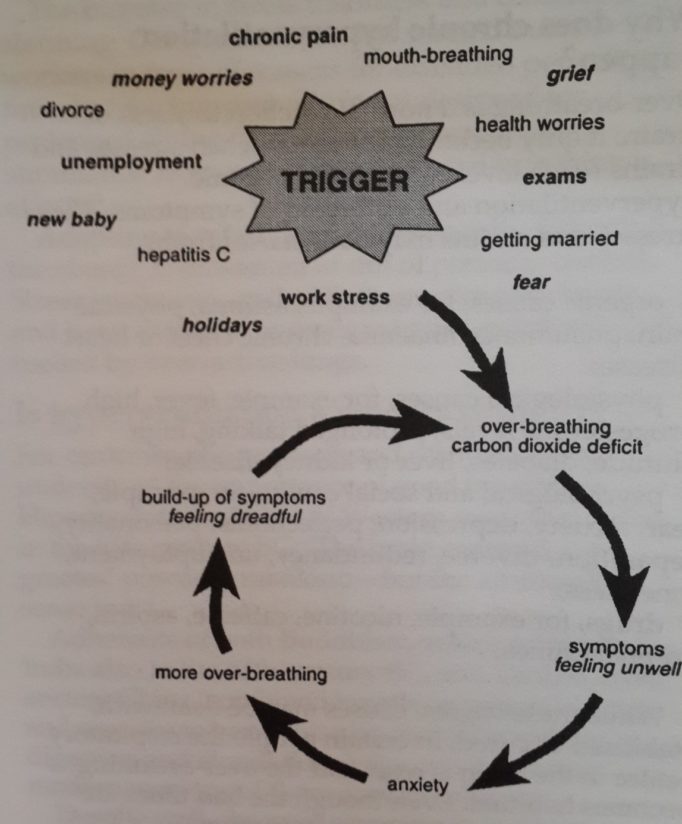

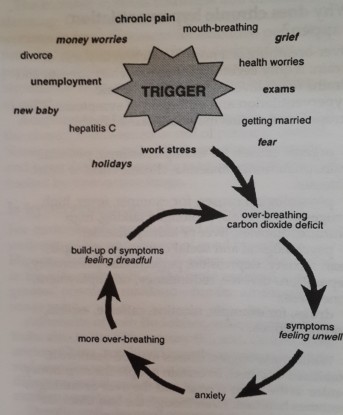

Over-breathing is a normal reaction to stress or strain: it only becomes abnormal when stresses and strains reach levels that lead to chronic hyperventilation and outbreaks of symptoms. These stresses and strains may have started from:

- organic causes, for example, asthma, physical pain, pneumonia, anaemia, chronic chest or heart disease;

- physiological causes, for example, fever, high progesterone levels, prolonged talking, high altitude, diabetes, liver or kidney disease;

- psychological and social causes, for example, fear, anxiety, depression, perfectionist personality, separation/divorce, redundancy, unemployment, loneliness;

- drugs, for example, nicotine, caffeine, aspirin, amphetamines.

While these original causes may be dealt with, stabilised or cured, in certain people the respiratory centre in the brain is reset and the over-breathing becomes habitual. Even though the bad times are over, the increased breathing rate stays.

World-wide, the 1990s have been a decade of change and uncertainty. Our minds evolved in an ancestral environment that lacked the Pressure, noise and speed of the present electronic age.

we’re constantly bombarded with information and our brains often can’t cope with it all. We need to consciously take time out to counter this megastimulation, but few of us do.

The increase in stress disorders and diseases is alarming. Computerisation has pinned many workers in front of screens for extended periods of time, but the human body is not designed for prolonged sitting. We experience maximum stimulation from minimum effort and breathing is affected.

Adapting to rapid change is especially difficult if the change is unwanted or out of personal control. Stress levels soar, and with them adrenalin levels and heart rate, and nervous exhaustion follows – all fuelled by over-active lungs.

Is hyperventilation a modem disorder?

For centuries philosophers and scientists have understood the importance of good breathing. Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, noted in the fifth century BC: ‘The brain exercises the greatest power in mankind – but the air supplies sense to it’

Adherents of both Buddhism, which originated in India also in the fifth century BC, and Taoism, from ancient China, combined breathing with relaxation and exercise to harmonise heart rate, breathing, digestion and circulation. Yoga and t’ai chi are modem versions of these ancient wisdoms.

Despite well-observed accounts in Western literature of ‘breathless’ heroines or heroes with their ‘breath taken away’, little was understood about the link between over-breathing and ill- health. The first detailed medical description of

hyperventilation was not published until 1871, in a study of 300 American Civil War soldiers. A doctor noticed ‘disabling shortness of breath, irritable heart and oppression of breathing’ and thought the cause of these problems lay in the heart.

Around the turn of the century other medical researchers experimented with normal subjects, asking them to hyperventilate voluntarily; their results noted neurological effects (tingling and muscles spasms) as well.

The term hyperventilation syndrome (HVS) was coined in the 1930s. One British physician called it ‘one of the commonest chronic afflictions of sedentary town dwellers’. Breathing into a paper bag (re-inhaling carbon dioxide-rich air) became a popular treatment for acute attacks of HVS at this time.

No theatre would be without a paper bag in the wings ready for stage-fright victims, frozen in respiratory alkalosis (terror) while awaiting their cue. However, while the paper bag method may be useful in helping with acute panic attacks, it is of no use to chronic over-breathers. It may temporarily restore normal blood gases, but it does nothing to correct the underlying cause – breathing pattern disorders.

It is extremely dangerous during an acute asthma attack to tiy to control rapid wheezy breathing using a paper bag. Increased drives to breathe normal during an attack. It is on record that at least one person has breathed their last into a brown paper bag.

Recent medical research has revealed more about the physiological system derangements, metabolic imbalances and anxiety-related symptoms caused by habitual over-breathing, but it is still an underrecognised and under-treated disorder.

Whether it is primarily a mental or a physical health problem has been hotly debated. Fortunately, the move towards holistic medicine, in which body and soul are treated together, has been of benefit to the vast number of people suffering from chronic hyperventilation and to their doctors, who can add this distressing disorder to their diagnostic repertoire.

I had a medical file as thick as a phone book and I always seemed to be at the doctors having tests for this and that. Nothing was ever found to be really wrong. But a locum picked it straight away. My breathing was grossly askew and my symptoms were a result of this. At last I had something to work on.

Dr. Mike Thomas

Related Posts

![Garlic Ginger Chicken [ Medium ]](https://www.womenplatform.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Garlic-Ginger-Chicken2-480x2631-150x150.jpg)